KEY POINTS

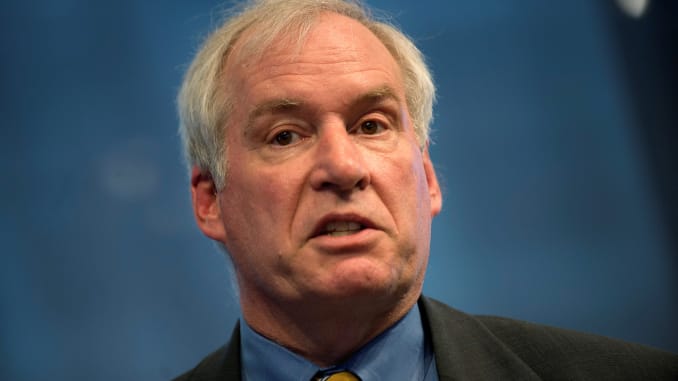

- Boston Fed President Eric Rosengren said years of low interest rates that encouraged risk-taking are making the current economic downturn worse.

- He specifically cited “low rates persisting for an extended period even after the economy has made progress in the recovery” that can create problems.

Years of low interest rates led to excessive risk taking in commercial real estate and will make the current economic downturn even more severe, Boston Federal Reserve President Eric Rosengren said Thursday.

The central bank official said he expects a wave of defaults and bankruptcies to hit that will aggravate an unemployment problem that has hit lower-wage workers disproportionately.

Regulatory authorities, he added, should have been able to see conditions building up that would make any unexpected crisis worse.

“Clearly a deadly pandemic was bound to badly impact the economy,” Rosengren said. “However, I am sorry to say that the slow build-up of risk in the low-interest-rate environment that preceded the current recession likely will make the economic recovery from the pandemic more difficult.”

The Fed has been at the center of the coronavirus pandemic crisis response, slashing already-low interest rates and implementing a slew of programs to ensure market functioning and lend money to areas of the economy in need.

In recent days, it has adapted an even more dovish approach to monetary policy, pledging not to raise rates even if inflation runs above the Fed’s preferred 2% target.

A loose Fed also often finds itself the target during times of excess, like the financial crisis and the dotcom bubble. Rosengren’s remarks reflected concern about the consequences of the low rates that have prevailed for the past dozen years.

He noted that commercial real estate firms have “gradually increased risk by taking on more leverage, which magnifies returns with good outcomes – but also magnifies losses when bad outcomes occur.

“This increase in risk-taking is more likely to take place in a low-interest environment, like the one which prevailed in the aftermath of (and as a result of) the financial crisis and Great Recession.”

He specifically cited “low rates persisting for an extended period even after the economy has made progress in the recovery” as was the case when the Fed held its benchmark short-term lending rate near zero for more than six years after the Great Recession ended in 2009.

In those times, “businesses and firms take on additional debt and accumulate more risky assets in search of better returns – potentially bidding up asset prices to unsustainable levels,” he said.

Consequences from that climate are likely to be felt soon with looming debt defaults and business failures he said, adding that the impact on banks, particularly smaller institutions, is likely the reason for the sector’s stock market underperformance.

He also spoke about the impact on employment, particularly workers in the services industries who have taken the hardest hit during the current downturn.

“The build-up in risks in commercial real estate, and leverage in the corporate sector, prior to the COVID-19 pandemic are likely to result in more bankruptcies and higher unemployment during this crisis than if less risk had been taken,” he said.

While banks currently have strong capital positions, lending standards are tight. Rosengren said the financial system’s placement at the center of multiple economic crises should cause officials to consider the implications of “reach-for-yield” environments.