China is paying a heavy toll for its efforts to punish Australia by banning or restricting certain commodity imports, while conversely Australia seems to have avoided any serious financial ramifications so far.

It is perhaps surprising that the authorities in Beijing, having witnessed how the trade war launched by former U.S. President Donald Trump backfired on his own country, would be keen to try the same thing on Australia.

Trump tweeted in March 2018, as his administration was ramping up its tariffs against Chinese goods that “trade wars are good, and easy to win”.

It turns out that he was somewhat right, but only in the reverse of what he expected, insofar as the country that launches the trade war tends to be the loser, and the country that is the intended target seems to prosper.

Coal is the highest-profile Chinese target in the Australia row. Beijing effectively all but banned imports from Australia as part of its efforts to pressure Canberra on several issues, ranging from Australia’s call for an international investigation into the origins of the coronavirus pandemic to the decision to block Huawei from Australia’s 5G network rollout.

China’s imports of Australian coal have collapsed, with Refinitiv vessel-tracking and port data showing just 687,000 tonnes were discharged in December, down from the 2020 peak of 9.46 million tonnes in June.

But the data also show that Australia’s overall exports haven’t really suffered, with December shipments of 33.82 million tonnes being the best month in 2020.

While the cold snap across north Asia boosted demand from Japan, South Korea and Taiwan, it also appears Australia has managed to ship more coal to other regional consumers, such as India, Vietnam and Thailand.

Coal is more than just a volume story, with prices moving in favour of Australia and against China.

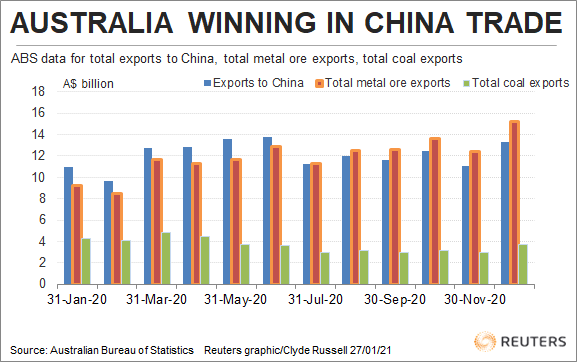

Australia’s coal exports were worth A$3.7 billion ($2.87 billion) in December, the most since May last year, according to data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics.

The benchmark Australian thermal coal price, the Newcastle Weekly Index, as assessed by commodity price reporting agency Argus, ended at $87.52 a tonne on Jan. 22. That was up 89% from its 2020 low of $46.37, reached in September, at a time when market concern over the impact of China’s effective ban on imports was highest.

The rise in seaborne coal prices has made it more expensive for China to buy imported coal. In turn, that has allowed domestic prices to remain elevated as they aren’t facing competition from overseas producers.

The price of thermal coal at Qinhuangdao has retreated in recent days, ending at 873 yuan ($135.14) a tonne on Jan. 26, down from the recent high of 1,038 yuan.

But even with the recent drop, the Chinese benchmark is still some 87% higher than the 2020 low of 467 yuan a tonne from May – well above the 520-570 yuan range believed to be preferred by the authorities as it ensures mines remain profitable but fuel costs for utilities aren’t too high.

IRON ORE, COPPER

It’s not just coal where Australia seems to be more than holding its own in the trade dispute: exports of cereals rose to A$1.19 billion in December, the highest on record and almost three times the value of shipments in November.

China imposed an 80.5% tariff on imports of Australian barley in May last, collapsing the trade between the two nations. But while Australian barley farmers were initially hit hard, they have successfully managed to switch to alternative markets or plant other crops.

China also has an unofficial ban on imports of copper ores and concentrates from Australia, which had been its fifth biggest supplier.

However, a global shortage of mined copper ores means China is being forced to pay more for supplies. At the same time its smelters are having to pay less for treatment and refining charges, as they struggle to source material.

Again, what has happened is that China has cut itself off from a source of supply at a time of global shortage. It has imposed costs on itself and no penalty on Australian copper miners, who can sell easily to other buyers.

China hasn’t mandated any restrictions on the most important commodity it buys from Australia, namely iron ore. But it is having to pay handsomely for buying the steel-making ingredient given supply issues in Brazil, the second-largest exporter behind Australia.

Australia’s exports of metal ores, which include iron ore and copper, rose to a record A$15.2 billion in December, up 22.6% on November, according to official statistics.

Overall, Australia’s exports to China were A$13.34 billion in December, the highest since June, reflecting strong demand for iron ore, liquefied natural gas and some agricultural commodities.

Since China started its trade actions against Australia, the numbers seem to be tilting heavily in favour of Canberra.

This supports the lesson from the U.S.-China trade dispute: if you still need the products you are targeting for tariffs or import bans, it will cost more to source them from other suppliers.