KEY POINTS

- As the economy struggles to shake off the pandemic effects, worries are growing that the recovery could look like a K.

- That would be one where growth continues but is uneven, split between sectors and income groups.

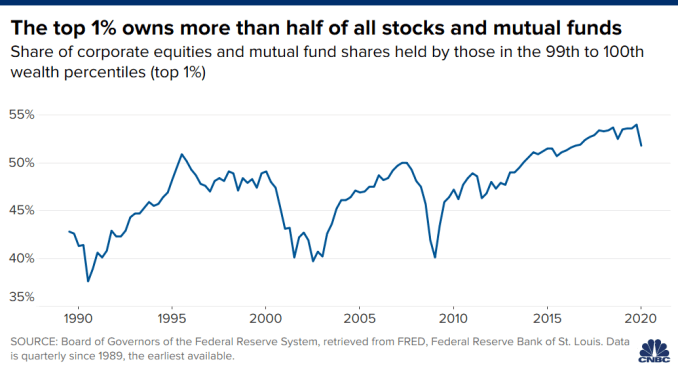

- One obvious area of concern is the dichotomy of the stock market vs the real economy, especially considering that 52% of the market is owned by the top 1% of earners.

- “Let’s not get lost on different letters of the alphabet,” Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin said. “There are certainly parts of the economy that need more work.”

The story for much of the past generation has been a familiar one for the U.S. economy, where the benefits of expansion flow mostly to the top and those at the bottom fall further behind.

Some experts think the coronavirus pandemic is only going to make matters worse.

Worries of a K-shaped recovery are growing in the alphabet-obsessed economics profession. That would entail continued growth, but split sharply between industries and economic groups.

It’s a scenario where big-box retail and Wall Street banks benefit and mom-and-pop shops and restaurants and other service profession workers lag. Though not readily visible in GDP numbers for the next several quarters that will look gaudy in historical terms, the uneven benefits of the recovery pose longer-term risks for the national economic health.

“The K-shaped recovery is just a reiteration of what we called the bifurcation of the economy during the Great Financial Crisis. It really is about the growing inequality since the early 1980s across the country and the economy,” said Joseph Brusuelas, chief economist at RSM. “When we talk K, the upper path of the K is clearly financial markets, the lower path is the real economy, and the two are separated.”

Indeed, one of the simplest ways to envision the current K pattern is by looking at the meteoric surge of the stock market since late March, compared to the rest of the economy. While the market soared to new heights, GDP plunged at its most ever at an annualized rate, unemployment, while falling, remains a problem particularly in lower income groups, and thousands of small businesses have failed during the pandemic.

That in itself exacerbates inequality at a time when 52% of stocks and mutual funds are owned by the top 1% of earners.

But it’s not just about asset ownership, it’s the nature of those assets.

The stock market gains have been largely the result of a handful of stocks. Excluding newcomer Salesforce.com, Apple, Microsoft and Home Depot have contributed more points to the Dow Jones Industrial Average this year than the other 27 stocks on the index combined.

That’s why Wall Street when looking for the proper letter — V, W, U or variations thereof — is beginning to see K as more of a possibility.

“The K-shaped narrative is gaining traction as the tale of two recoveries conforms well with the ongoing outperformance of risk assets and real estate while front-line service sector jobs risk permanent elimination,” Ian Lyngen, head of U.S. rates strategy at BMO Capital Markets, said in a note.

The dominating stocks, in fact, help tell a story about a shifting economy that is leaving those behind with less access to the technology that will shape the recovery.

“We believe this is now settled and that we are seeing a ‘K-shaped’ recovery,” wrote Marko Kolanovic, global head of macro quantitative and derivatives research at JPMorgan Chase.

Kolanovic, who has foreseen a number of major market changes, said the rapid evolution of society during the pandemic has triggered movements that have exacerbated inequality.

“The use of devices, cloud and internet services was bound to skyrocket while the rest of the economy took a nose dive (airlines, energy, shopping malls, offices, hospitality, etc.),” he said. “This has created enormous inequality not just in the performance of economic segments, but in society more broadly. On one side, tech fortunes reached all-time highs, while lower income, blue collar workers and those that cannot work remotely suffered the most.”

Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell has bemoaned the momentum that lower earners had just begun to see prior to the pandemic.

That’s one of the reasons the central bank last week adopted a major policy shift in which it will allow inflation to run above the Fed’s 2% goal for a period of time after it has run below the mark. More than just a philosophical statement about inflation, codifying the approach allows the Fed to keep interest rates low even after the jobless rate drops below what had once been considered full employment.

Fed officials believe that keeping policy loose when the unemployment rate hit a 50-year low over the past year helped contribute to the wider distribution of income gains, and should be the approach going forward.

“It’s a good start that the Federal Reserve, based on two decades of structural change in the economy and a rapidly changing demographic structure in the United States, decided to walk back its long-held preference to act to preventatively against inflation, when expectations were clearly anchored,” Brusuelas said.

The Fed, though, has taken some of the blame for the inequality by implementing policies that seem to benefit asset holders and ignore the rest of the population. While loans to smaller businesses have been slow to get out, the central bank has been buying junk bonds and debt of big companies like Apple and Microsoft to support market functioning. The inflation pivot and an accompanying change on the approach to the unemployment rate, then, is seen as a way to focus policy more broadly.

A variety of paths

To be sure, the actual shape of the recovery depends on a number of factors, high among them the direction of the virus and the extent to which Congress and the White House come through with more fiscal aid.

This downturn is unique in that it did not follow one of the usual paths lower, such as a credit crunch or an asset bubble. Instead, this was a government-induced recession, a byproduct of efforts to contain the pandemic by purposely keeping people away from their jobs and subsequently greatly reducing the ability of businesses to operate.

That’s why predicting the path of recovery is difficult.

“Every business cycle since 1990 has been one where there’s been some ‘K’ characteristics to it,” said Steven Ricchiuto, U.S. chief economist at Mizuho Securities. “Because they’ve been credit cycles, rising waters don’t always lift all boats the same way. Some boats are tiny little lifeboats without much baggage, and some other boats have heavier bags that need more energy to lift. Those are the ones that have credit problems.”

In the current situation, credit is not the problem and the Fed has backstopped any of those issues that may arise through its myriad lending and liquidity facilities.

Ricchiuto sees a “more traditional recovery environment” that will turn into a “swoosh,” or one where an initial burst levels off. That also is a popular view.

“Clearly some areas are going to be slower to come back. That’s going to be true even when the vaccine comes about,” said Yung-Yu Ma, chief investment strategist at BMO Wealth Management. “I don’t buy into the K shape so much. I think it’s more a matter where there will be some industries that take an extra six to nine months to really pick up economic momentum. But once that happens, everything will go together in the same general trajectory.”

Economic data generally reflects a multi-speed recovery. The Citi Economic Surprise Index, which measures data points against Wall Street expectations, is well above any level that it had seen pre-crisis. Hiring finally has picked up in bars and restaurants as well as retail establishments, but is well behind pre-pandemic levels and dependent on a slew of intangibles ahead.

“We went into this downturn without having severe imbalances in the economy that needed to be corrected,” Ma said. “The external shock, yes, it’s dramatic and one that requires a lot of effort to get past and a lot of time and resources. But it’s not the case that the underlying fundamentals of the economy were distorted.”

Still, worries that uneven growth could accelerate wealth disparities are on the minds of some economists and elected officials, in the latter case becoming particularly acute as the heat turns up on election season.

The subject came up on multiple occasions during a hearing Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin had before a House panel on the coronavirus earlier this week.

“Rather than a V-shaped recovery, economists have warned we face an uneven K-shaped recovery, where the wealthy quickly bounceback to pre-pandemic prosperity while lower-income families continue to suffer economic harm,” Rep. James Clyburn (D-S.C.) told Mnuchin.

The Treasury secretary said the administration is sensitive to the issue though he insisted that “we are set for a very strong recovery.”

“I just want to assure you the president and the administration thinks there is more work to be done,” Mnuchin said. “Let’s not get lost on different letters of the alphabet. Let’s move forward on a bipartisan basis on areas we can agree upon. Because there are certainly parts of the economy that need more work.”