World market prices of gold – viewed by investors as a safe store of value in uncertain times – have surged to levels last seen in 2012, and are up 16% this year.

But millions of subsistence workers, who typically use rudimentary techniques at unregulated mines, have received none of the benefits as pandemic disruption to supply lines has shrunk their already sporadic earnings.

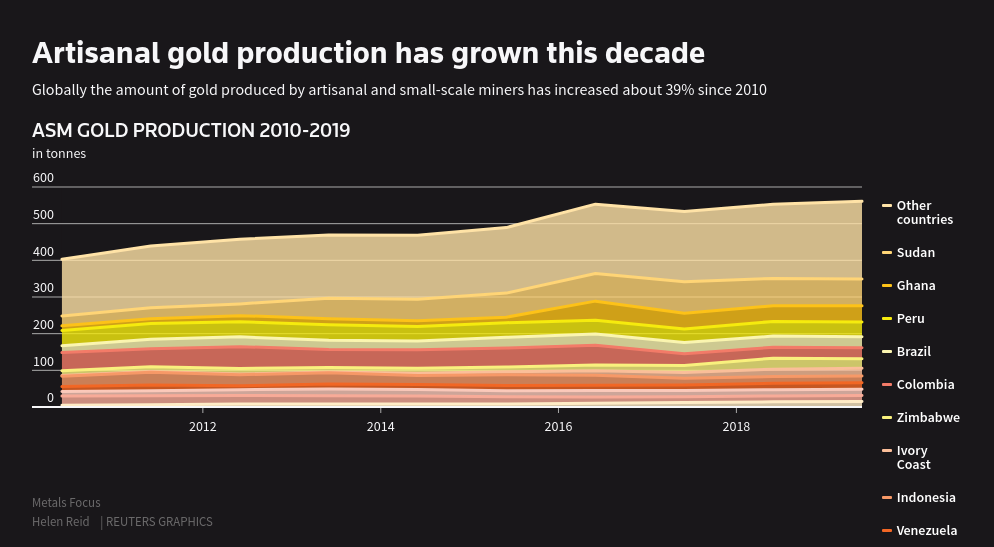

The World Bank is creating a dedicated emergency relief fund for the estimated 40 million artisanal and small-scale miners (ASM) worldwide, three sources told Reuters on condition of anonymity.

A World Bank spokeswoman confirmed the fund, which was yet to be officially launched. She said the fund would “provide short-term assistance to artisanal mining communities to better cope with COVID-19 impacts”.

Donors have contributed $5 million to the fund, and the Bank aims to expand it to $15 million. That money would be disbursed to projects helping miners across geographies and minerals.

“This is very rare because usually disaster recovery funding is not specifically directed to ASM as a uniquely vulnerable livelihood group,” said one consultant, who declined to be named.

The Canada-based Artisanal Gold Council (AGC), an NGO, is trying out a project to help communities dependent on small-scale gold mining in Burkina Faso.

With 40% of the population living below the national poverty line, the country is particularly vulnerable.

The AGC has bought gold direct from miners at the pre-pandemic going rate, and is exporting it to PAMP, a London Bullion Market Association (LBMA) certified refinery in Switzerland.

PAMP declined a request for an interview, and did not reply to written questions from Reuters.

The gold, sourced from five artisanal miners around the southern town of Dano, was transported to the capital, Ouagadougou, and was in the process of being certified for export by the mines ministry.

The initial export, of 800 grammes of gold (worth around $48,847), is a trial. Depending on its success, the AGC plans to source a further 20kg from Burkina Faso, and then begin sourcing from Colombia too.

Aboubakar Dabire, a miner who sold 500 grammes of gold to the AGC, said: “My community was really hard hit by COVID-19. When gold prices are low, everything is undermined.”

“People will take this [scheme] seriously as it is a well-organised system,” Dabire added. “It means they will make an effort to avoid certain buyers in the field who are ruining the market.”

Attempts to formalise artisanal mining, stamp out child labour, and sever links with illicit minerals trade face significant obstacles.

In remote artisanal gold mining communities, trade is largely informal and the rigorous documentation required by LBMA guidelines is hard to enforce.

These guidelines require gold refineries to verify where their gold is mined, show it does not fund conflict or armed groups, collect “Know Your Customer” information on the whole supply chain, and verify all legal taxes have been paid.

It took the AGC two months to complete the process.

The challenges help to explain why only a tiny share of the gold produced worldwide is “London Good Delivery” certified by the LBMA. In Africa, 1.6% of gold is.

The effort and cost required to implement these standards and bring artisanal gold into formal channels mean other NGOs do not consider direct market intervention, such as that being done by AGC, viable.

“We are very aware that [gold] prices are depressed for local miners, but we are not convinced the international market is the route to go down,” David Finlay, responsible minerals manager at the Fairtrade Foundation, said.