KEY POINTS

- There are increasing signs that the British public are growing frustrated with the restrictions, with anti-lockdown protests hitting the capital at the weekend.

- The vaccination rollout has been a silver lining in a pandemic that hit the U.K. hard.

When the first coronavirus lockdown was imposed across the U.K. exactly a year ago, most would have struggled to conceive that, 12 months on, restrictions on public and private life would still be in place.

With that now a reality, there are increasing signs that the British public are growing frustrated with the constraints, with anti-lockdown protests hitting the capital at the weekend.

Although the U.K. has laid out a roadmap for the lifting of restrictions, with the government aiming to ease most Covid curbs by June 21, there have been smoke signals over the last few days that the government doesn’t expect normal life to resume even then.

Government ministers, and health experts advising them, have made a number of comments suggesting that summer vacations are now “highly unlikely” given the situation in other parts of Europe where coronavirus cases are rising due to new variants of the virus.

Another health expert — the head of immunization at Public Health England — suggested Sunday that masks and social-distancing measures could be required for several years.

The government has also signaled it wants to extend its authority to reverse any easing of measures and, thanks to support from the opposition Labour party, is expected to receive approval to extend emergency powers until October, despite a group of lawmakers within the ruling Conservative Party describing the move as “authoritarian.”

Combine these factors and a summer of freedom for the U.K. public is starting look more unlikely, potentially setting the stage for more public discontent as Brits become desperate to return to “normality.” Especially as the vaccine rollout continues at pace; on Saturday, a record-breaking combined total of 844,285 first and second doses were given to those in line for the shot, up from 711,157 people receiving a vaccine dose on Friday.

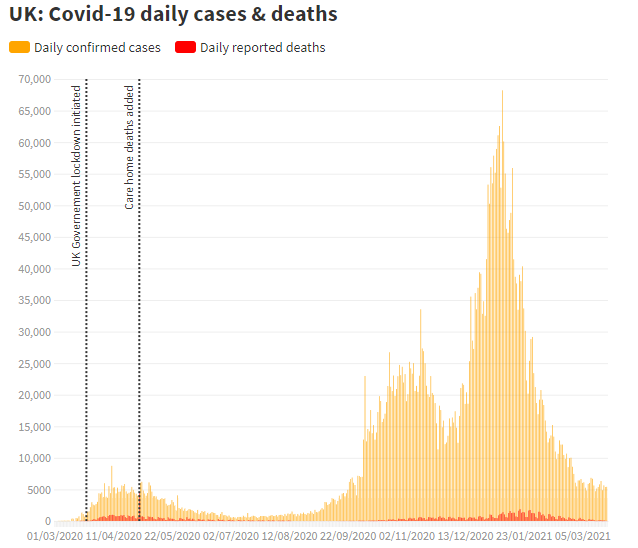

The toll on the UK in numbers

March 23 is the first anniversary of Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s announcement to the British public that the country would go into lockdown, with the government implementing unprecedented measures in peacetime that were designed to stop the spread of the coronavirus that had first emerged in the then-largely unheard of Chinese city, Wuhan, in December 2019.

Then, when Johnson made the first “stay-at-home” announcement, one that citizens have now become used to, the U.K. had reported a daily jump in the number of deaths caused by the virus, with 335 fatalities over 24 hours with hospitals and health care staff grappling to understand Covid-19 and effective treatments.

Fast forward a year and the U.K. has the ignominious position of having recorded the fifth-highest number of coronavirus cases in the world, after the U.S., Brazil, India and Russia, according to a tally from Johns Hopkins University. To date, the U.K. has reported over 4.3 million infections, and over 126,000 deaths — the fifth highest number of deaths globally after the U.S., Brazil, Mexico and India.

A minute’s silence will be held in the U.K. on Tuesday to reflect on the deaths caused by the virus.

Prime Minister Boris Johnson said in a statement that “the last 12 months has taken a huge toll on us all, and I offer my sincere condolences to those who have lost loved ones.” He added that the country had shown “great spirit shown by our nation over this past year.”

The reasons behind the higher death toll in the U.K., compared to its continental counterparts in mainland Europe, are manifold but underlying factors include a higher rate of obesity, preexisting health conditions and socio-economic factors.

What went wrong, or right?

The government, for its part, has come in for intense criticism that it locked down too late, failed to implement border controls and checks on incoming travelers to the U.K., did not adequately protect health care workers and presided over an inadequate test and trace system still considered sub-par. In sum, it’s been accused of not being prepared for a pandemic, and for mismanaging one when it arrived.

One bright spot, and a saving grace, has been the U.K.’s highly-regarded scientific community which has been at the forefront of research into the virus, its effects and trials looking at the best way to combat it. In June 2020, for example, U.K. health experts led by the University of Oxford discovered that a low-cost steroid treatment, Dexamethasone, could greatly lower the risk of death when given to the most critically-ill Covid patients.

An even bigger breakthrough came when the University of Oxford and Anglo-Swedish pharmaceutical AstraZeneca, successfully developed and trialed one of a handful of effective vaccines, with the shot’s creation even more remarkable given that it can take years to develop vaccines. U.K. vaccine research was boosted by government funding too.

The U.K. was the first country in the world to approve and deploy the Pfizer–BioNTech vaccine back in early December, and quickly initiated a national immunization program that has gathered pace.

In January, the AstraZeneca vaccine was added to the arsenal and the vaccination program went from strength to strength, surprising even the most cynical Brits and winning the country’s heath experts and National Health Service plaudits for the bold decision-making, and a well-managed rollout.

Unlike other countries in Europe, who erroneously questioned the AstraZeneca vaccine’s efficacy in the over-65s, the U.K. went ahead with mass immunizations with the elderly and health care workers prioritized.

Health experts also took the view (criticized at the time but now replicated in other countries) that the gap between the first and second doses of the coronavirus vaccines being deployed should be elongated up to 12 weeks in order to offer more initial protection to more people.

The decision was vindicated by later clinical data showing that the strategy was effective and even increased the efficacy of the AstraZeneca vaccine. The rollout has exceeded expectations; as of March 20, over 27.6 million British adults have received a first dose of a vaccine, and over 2.2 million have had their second shot, according to government data.

There is palpable restlessness among members of the public — particularly those opposed to lockdown in the first place — as well the business community, for society to reopen. Anti-lockdown protests in London last weekend attracted several thousand demonstrators who chanted “Freedom!” as they marched through the capital. Later, scuffles between the police and demonstrators led to over 30 arrests.

What happens next?

So, when it comes to the vaccine, it has been a case of “so far, so good.” The U.K. has seen the benefit with the number of new cases, hospitalizations and deaths steadily decreasing.

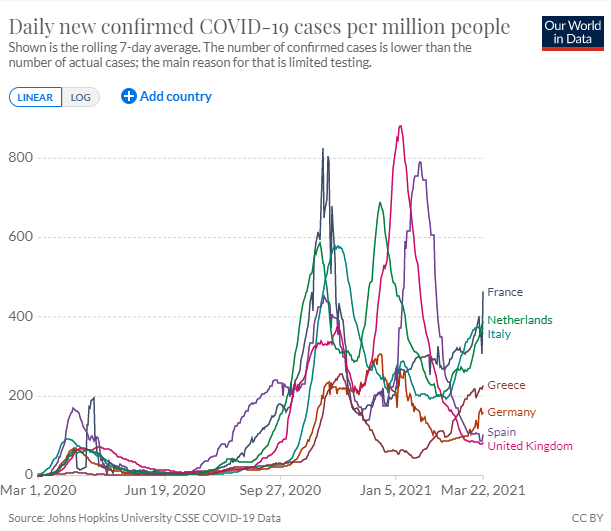

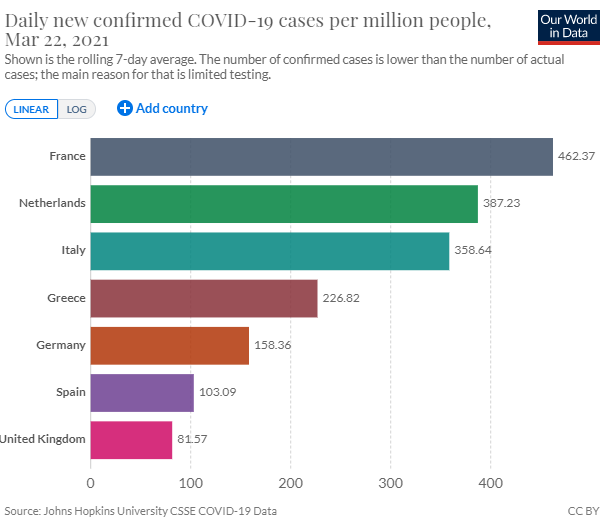

The speed of the rollout has been seen as critical, at a time when new variants of the virus have emerged and threatened to potentially undermine the positive effects of the vaccines.

Mainland Europe is seeing the ramifications of its perhaps understandably slower rollout given the fact that the EU chose to order vaccines as a bloc and, crucially, ordered later than the U.K. and U.S.

As well as slower supplies and production issues, the EU has had to contend with vaccine hesitancy, which is not prevalent in the U.K., and bureaucracy, again a factor not so much of an issue in Britain where the health care service is largely a joined-up and well-connected centralized system.

But this week the U.K. faces a potential challenge to its rollout if EU leaders, meeting virtually Thursday, decide to block exports of Covid vaccines made in the bloc to countries, like the U.K., that are further ahead in their immunization programs.

Johnson has reportedly sought to allay such a move, speaking to his counterparts in France and Germany at the weekend. But if the EU goes ahead, the U.K. could face further supply bottlenecks; it is already expecting a supply shortage due to a reported delay in exports from an Indian manufacturing facility.

Delays could cost Britain its so-far successful rollout, and citizens their liberties, although the government has so far said it still plans to have offered a first dose of a vaccine to all adults by July 31.