The South African Reserve Bank (SARB) cut its main repo rate by 25 basis points on Thursday, surprising the vast majority of economists.

Policymakers voted unanimously to cut the key rate from 6.5% to 6.25%, upending the expectations of 21 of the 24 economists polled by Reuters ahead of the decision.

Facing a raft of challenges, including delays in reforms to teetering state-owned enterprises such as the heavily indebted Eskom electricity monopoly, escalating government debt and depleted business confidence, Africa’s most industrialized economy has struggled to exit a period of anemic growth which embedded itself under previous President Jacob Zuma. The South African economy contracted in the third quarter of 2019.

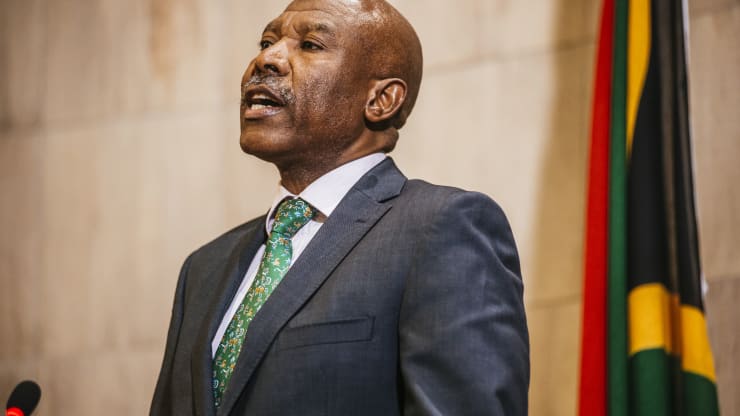

The decision to cut rates marks a significant shift in tone from the traditionally hawkish central bank, with Governor Lesetja Kganyago previously attributing slow growth primarily to supply-side constraints and arguing that loosening monetary policy would do little to boost activity.

A steady deterioration in economic performance has seemingly forced the SARB’s hand in considering new options. John Ashbourne, senior emerging markets economist at Capital Economics, suggested the decision will boost South Africa’s economy, creating a small upside risk to his 0.5% GDP (gross domestic product) growth estimate for 2020, but that this will remain below 1%. South African stocks climbed late last week in response to the decision.

In a note following the decision, Ashbourne projected that inflation will remain just below the 4.5% midpoint in the central bank’s target range for the first quarter of 2020, with economic figures likely to be even weaker than policymakers expect, leading to a further 25 basis point cut in March. Contrary to Governor Kganyago’s expectations, Capital Economics analysts believe the South African probably contracted in the fourth quarter of 2019.

Ashbourne also suggested that rising inflation means that the easing cycle will end after the expected March cut.

“The period of very weak inflation seen in (the fourth quarter) is unlikely to last. Oil prices have already jumped in recent months, and we expect that they will continue to strengthen over the duration of this year. Indeed, regulated petrol price decisions in December and January will significantly boost fuel inflation,” Ashbourne said.

South Africa’s last remaining investment grade sovereign credit rating is also in doubt, with Moody’s set to make its next announcement in March. A cut to a “junk” rating could cause a sharp decline in the rand.